A rigged financial system that systematically fuels inequality – this is how it works, why it must change, and how we may do that with Bitcoin

The title of this piece is a tribute to the book with the same name by Tarek El Diwany – a must-read on the moral and structural flaws of our financial system, which also served as a key inspiration for this article.

For most of us, money represents hard work, time and sacrifice. But for the financial elite, it’s something entirely different: a tool to extract wealth from society without creating anything of real value.

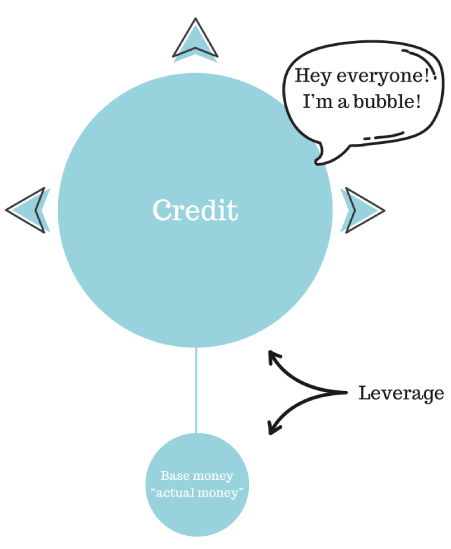

We live in a world where central banks control the issuance of base money (for the sake of not making this sound more sophisticated than it is, we’ll just borrow the term ‘actual money‘), while commercial banks issue credit (which is debt) out of thin air under a laissez-faire system. The result is a financial order that operates on an illusion, yet dictates the reality of our lives.

In this article, I’ll break down the fundamental mechanics that uphold the credit banking system, its primary product—fiat money—and the role of interest rates. But more importantly, I’ll reveal why this entire structure isn’t just flawed , but fundamentally unethical, and designed to siphon wealth from the many to the few.

- Base money = “actual money” issued exclusively by the government

- Credit = money issued by banks (through lending) in the form of debt

- Fiat money = broad term for money that can be issued without limitations, whether by governments or banks, at their discretion

The Most Profitable Business Idea in History

Banks operate under a business model where they create credit out of thin air when issuing loans, yet they charge interest on that credit as if it were actual money.

In other words, they lend money that did not previously exist (until they lent it out) and then collect a fee (the interest rate) for the privilege of borrowing it.

This system enforces an inflationary economic order – one in which the money supply must continuously expand.

Let me explain why in the simplest terms:

Imagine that the total amount of actual money in the world is $1,000. A bank loans out that entire sum as credit to a client at a 5% interest rate. After a year, the borrower must repay the initial amount ($1,000) plus the interest ($50), bringing the total repayment to $1,050.

Do you see the problem?

The borrower is required to pay back more money than actually exists in the system. Where does the extra $50 come from?

The simple answer is it can’t come from anywhere unless the bank (or some other bank) in the meantime expands the money supply by issuing a new credit loan to another borrower, hence injecting the necessary funds into circulation to enable repayment.

But now, the second borrower also owes their loan plus interest. The only way they can repay their debt is if yet another loan is issued, injecting even more money into circulation.

What we get from this, as you can see, is a money supply that by design must increase over time for the system to remain solvent. We get a type of money that is systematically diluted, eroding its purchasing power over time.

Making Money from Borrowing

Imagine now for a moment that you, as a borrower (not the bank), could take out a loan at an interest rate lower than the annual money supply expansion rate and invest that borrowed money into an asset that grows at the same rate as the money supply (such as real estate or an index fund).

What would that mean?

Well, it would mean you could make money simply by borrowing money.

Let me explain.

Suppose you take out a $1,000 loan from the bank at a 5% interest rate and invest it into an index fund that tracks the annual money supply growth rate of 10%.

- Each year, you owe the bank $50 in interest ($1,000 × 0.05).

- Meanwhile, your investment grows by 10%, increasing by $100 ($1,000 × 1.10).

By the end of year one, your investment has grown to $1,100, while your debt obligation remains $1,050 after interest.

After paying the $50 interest, you’ve pocketed $50 – simply for borrowing money.

But what’s even more noteworthy is that your investment compounds year over year.

- In year two, your new base amount is $1,100, so it grows by 10% again, reaching $1,210.

- Meanwhile, your interest payment remains fixed at $50.

Over time, your investment grows exponentially, while your interest payments remain tied to the original loan amount. This means that, eventually, you can repay the loan in full while still keeping the same amount in your investment account.

Crazy if that was possible, right?

The truth is that this isn’t just possible – it’s a structural reality of the system. Since new money must enter the economy to cover existing interest obligations, the rate of money expansion through credit must exceed the average interest rate charged on loans.

If it didn’t, borrowers collectively wouldn’t be able to repay their debts, and the entire system would collapse under the weight of its own obligations.

Put another way: if new loans are NOT issued at a large enough scale to keep servicing existing debt, the system collapses.

But if it’s the same rules for everyone – maybe it doesn’t matter?

Loans for the Rich, Debt Traps for the Poor

To understand why this structural reality is like having an ATM in your backyard for some and a destructive debt trap for others, we need to examine what determines who can get a loan and who can’t.

The key word is collateral.

But to arrive at the logical reason for why collateral exists in the first place, we first need to ask:

If banks truly have the power to create credit out of thin air, why wouldn’t they simply print money for themselves and go out and spend it in the market directly?

Wouldn’t that be the ultimate loophole?

The reason they don’t do this—though their practice of collecting interest is really only one step removed from it—is that if they issued credit and spent it themselves, they would lose ownership of those receipts.

What this means is that, instead of a borrowing client being obligated to repay their debt to the bank plus interest, the bank itself would become directly liable for redeeming the credit it had spent for actual money. Eventually, a withdrawal request would arrive, and given that the total amount of credit issued far exceeds the actual money (reserves) that banks hold (as we have already determined), this would risk triggering a bank run sooner rather than later.

A bank run occurs when trust in a bank suddenly evaporates, prompting a surge of clients attempting to withdraw their deposits all at once. Since banks cannot fulfill all withdrawal requests simultaneously—because the money doesn’t actually exist—this would effectively call their bluff, leading to insolvency and, if widespread, a systemic collapse of the entire economy.

To avoid this, banks are smart enough not to take on direct liability for the money they create and instead push that liability onto the borrowers as much as possible. Once a loan is repaid by a borrower, the bank simply erases the amount from its books—because, after all, it was never actual money to begin with—while stacking what remains: the interest payments as revenue.

However, even with this cunning setup, there remains a fundamental risk: borrower default. If too many borrowers fail to repay their loans, the bank’s solvency could be threatened.

This is where collateral comes into play.

To minimise the risk of losses like this, banks require borrowers to pledge valuable assets—such as real estate, stocks, or other property—as collateral. This way, if a borrower defaults, the bank can seize and liquidate the collateral to recover the outstanding debt.

Beyond the moral hazard of collateral-based lending—where banks may be incentivised to extend loans to clients they anticipate will default just to seize their assets—this system has entrenched the two-tiered financial reality we live in today.

Since access to loans under this arrangement is determined by how much collateral you own, those with the greatest assets are naturally granted loans at the lowest interest rates, allowing them to profit the most from borrowing.

Large corporations and the wealthiest individuals constantly secure loans at interest rates well below the rate of money supply expansion, effectively allowing them to grow their wealth simply by borrowing (like previously explained). Meanwhile, those at the other end of the spectrum—who lack substantial collateral—are forced to borrow at much higher rates, often 20%+ on credit cards, making it impossible to benefit from debt in the same way as the privileged.

As of this writing, the Federal Reserve’s benchmark rate (the effective cost at which banks obtain funds) sits at 4.33%*. The Prime Rate, which is the baseline interest rate that major commercial banks charge their most creditworthy corporate customers is likely only slightly above this benchmark – say, +1%. High-net-worth individuals with substantial assets to pledge as collateral can often access prime-equivalent rates through private banking. Meanwhile, everyday consumers with little to no collateral rely on credit cards with rates that start in the high teens (e.g., 17–18%) and extend into the mid-20s and above (e.g., 25–29%), depending on an applicant’s credit history and risk profile.**

Bank Runs and Bailouts

While banks do their best to push as much liability as possible onto their clients and uphold the illusion of solvency to avoid bank runs, history is riddled with bank failures.

The question is: Why do they happen? And are they unavoidable?

For the same reason that money expansion must exceed average interest rates to sustain the system, banks will inevitably fail to meet their obligations and collapse. It’s a structural reality – as new credit must be issued to cover previous interest payments, the system becomes increasingly leveraged. Over time, the gap between actual money (reserves) and total credit (debt) expands, making the system more fragile.

At a certain point, even minor disruptions—such as rising interest rates, natural events, or shifts in market confidence—will trigger widespread defaults and bank runs. It’s not a question of if, but when, given the structural reality of this system.

Regulatory measures may delay the inevitable, but they cannot prevent it. What’s also often overlooked is that these regulatory interventions—such as imposing higher collateral or income requirements by the government—may temporarily prolong the system’s stability (which some might argue serves society as a whole), but they do so at the cost of making access to profitable borrowing even more concentrated among the already wealthy (who have collateral).

The house of cards collapses

The big question really is: so what happens when the banks inevitably fail?

One might think this is finally the moment when the bluff is called – when the unsustainable business model that has allowed banks to create money out of thin air, profit from debt, and offload all liability onto others finally comes crashing down.

Is this the moment when they face the consequences – when, just like any reckless borrower, they are forced to pay for their mistakes?

Not even close.

Because banks have entangled the entire economy in debt, a banking collapse isn’t treated as a failure of their own making – instead, it’s framed as a national security crisis. And to be fair, in many ways, it is.

But not because the general public made it so.

It has become a national crisis—possibly even a global one—because banks have recklessly pursued an enterprise they knew was inherently unsustainable from the outset.

But that really doesn’t matter now. The result is that the government steps in, injects new money into the system, and bails out the banks to prevent a total meltdown.

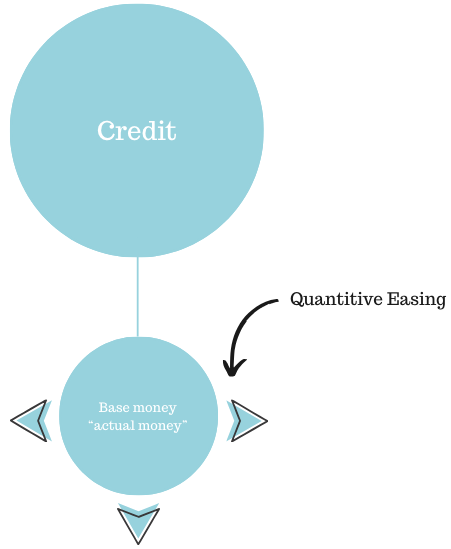

The bailout is done through a mechanism called Quantitative Easing (QE) – a term that sounds sophisticated, but simply means the government buys up the banks’ bad debts to keep them afloat.

It’s no different than the government stepping in to pay off your credit card bill after you’ve recklessly maxed it out to fund your own gambling habits. The only difference is that Main Street would never get the same treatment as Wall Street.

The bankers, of course, promise to never let it happen again – all while simultaneously cashing in record-breaking bonuses.

In the end, the general public foots the bill for the banks’ reckless risk-taking, the banks never learn their lesson, wealth inequality deepens – and as the sun sets on the horizon, the stage is quietly set for the same inevitable cycle to play out once again.

The Larger Cycle

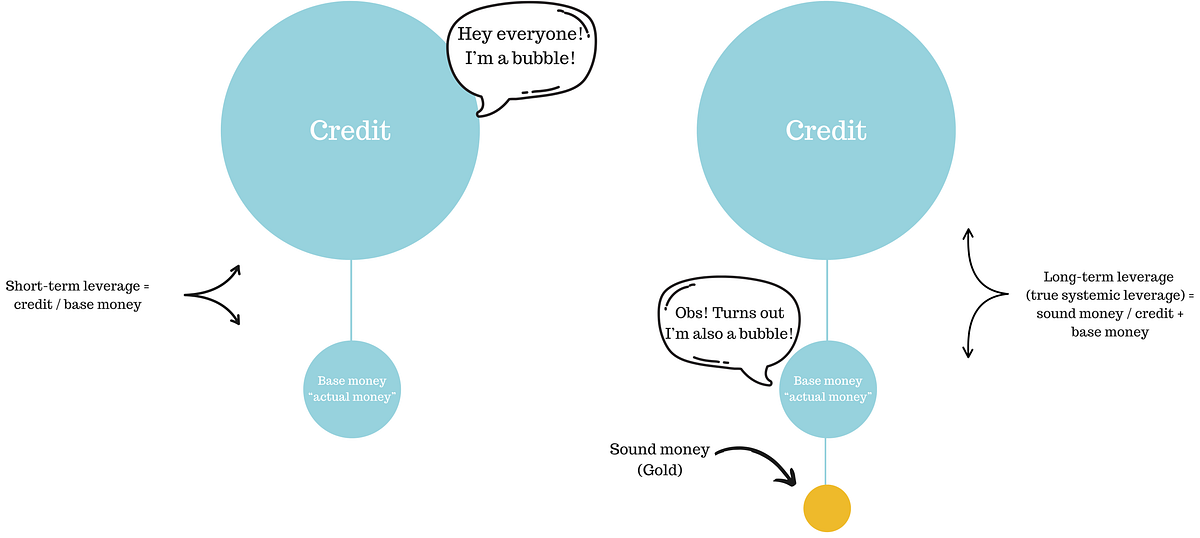

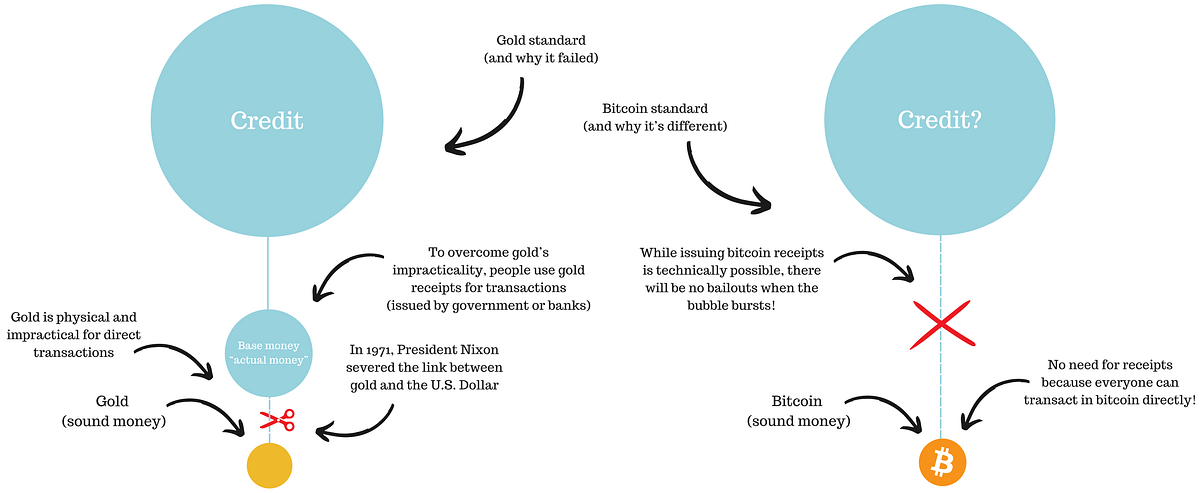

But here’s the thing – while some leverage was wiped out at the end of the previous cycle through austerity measures (by actually deflating the credit bubble), much of it was simply managed by expanding the supply of actual money (by inflating the small bubble). While this approach deleverages the economy in the short-term, it increases leverage in the long run.

This is because the true systemic leverage of the financial system isn’t really about the ratio between credit and actual money at any given point, but between sound money relative to credit plus actual money.

What is sound money?

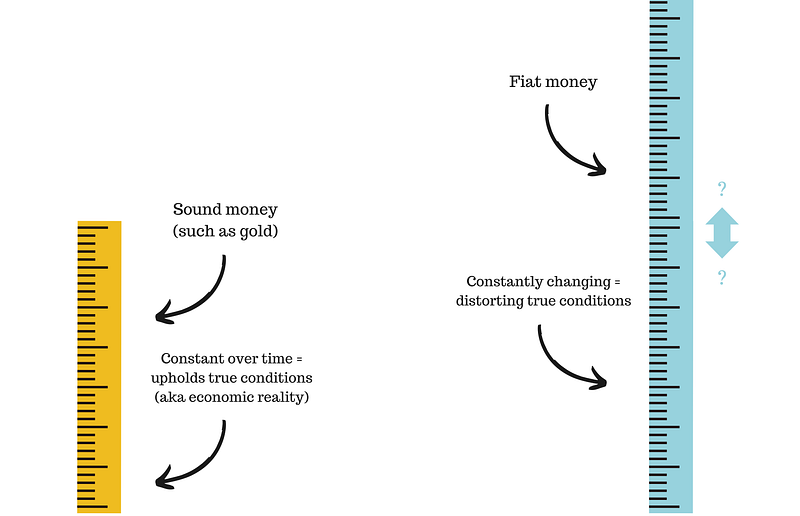

Sound money is money that cannot be arbitrarily expanded. Historically, gold served as the best example due to its limited supply and difficulty to mine. When money is sound, it accurately reflects the real supply of goods and services and the real demand for them. In other words, it simply acts as a measuring stick that is constant over time, ensuring that true conditions are clearly communicated to all participants at any given time.

Any deviation from sound money introduces a new moving variable—money itself—as a factor in determining prices. Moving away from sound money, then, into a form of money that constantly expands is the same thing as moving further and further away from true conditions.

While governments can temporarily expand the actual money supply relative to credit to maintain an illusion of stability, doing so suppresses the underlying reality – namely, that debt cannot be serviced forever with more debt, as it increases the true systemic leverage of the economy.

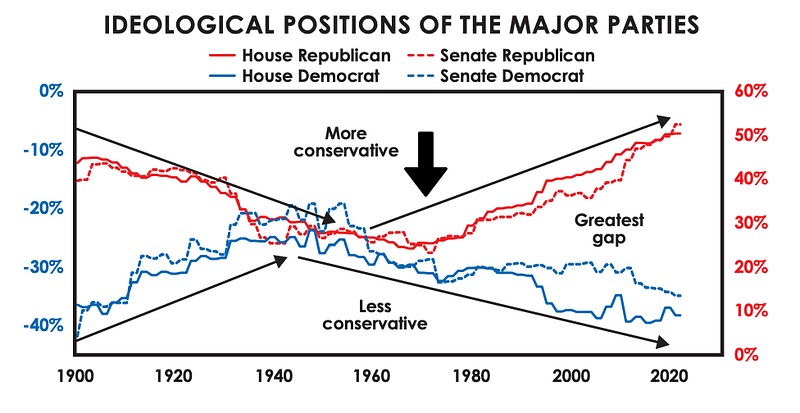

What this means in practice is that with each new small cycle that comes to an end, the distortions of the last aren’t really erased – they are merely transferred forward. The result is that polarisation deepens, accountability never happens, and wealth disparity compounds, stacking instability upon instability. The pressure keeps building, crisis after crisis, until eventually, enough of these “smaller cycles” have accumulated – and the outlines of a larger cycle begin to take shape.

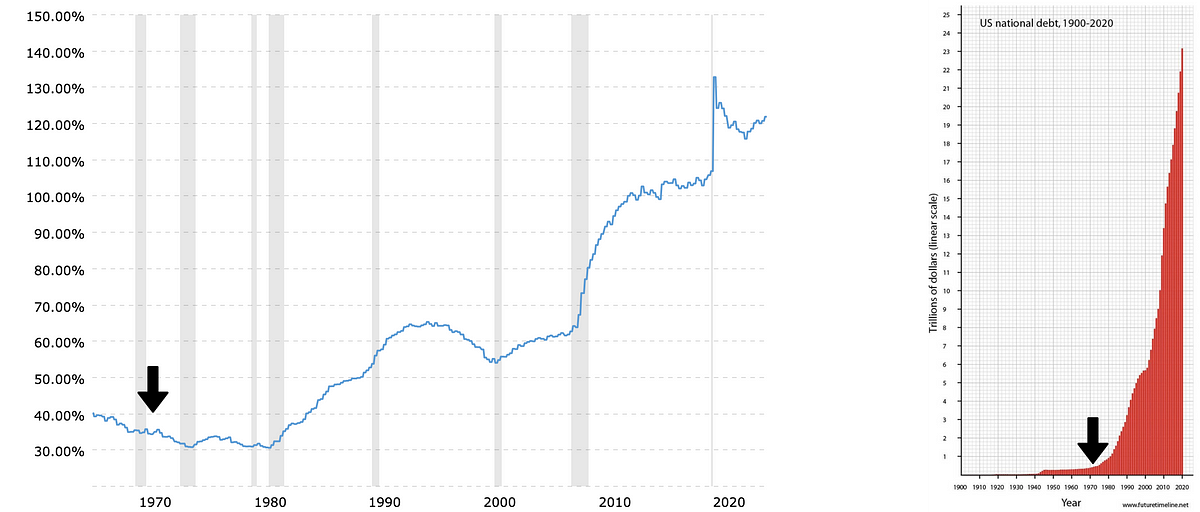

We can think of the ratio between credit and actual money as short-term leverage of the financial system, whereas indicators like national debt or the debt-to-GDP ratio as a proxy for the system’s long-term leverage (or true systemic leverage).

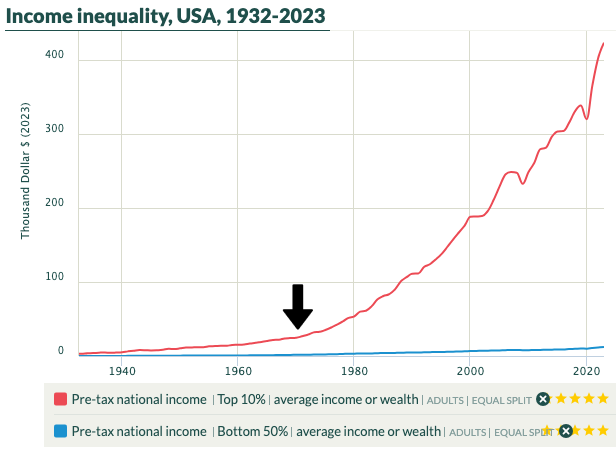

There’s an incredibly strong correlation between the financial system’s long-term leverage and wealth inequality – which, of course, is no coincidence given the direct cause-and-effect relationship I’ve laid out in this piece already.

Just look at the charts below.

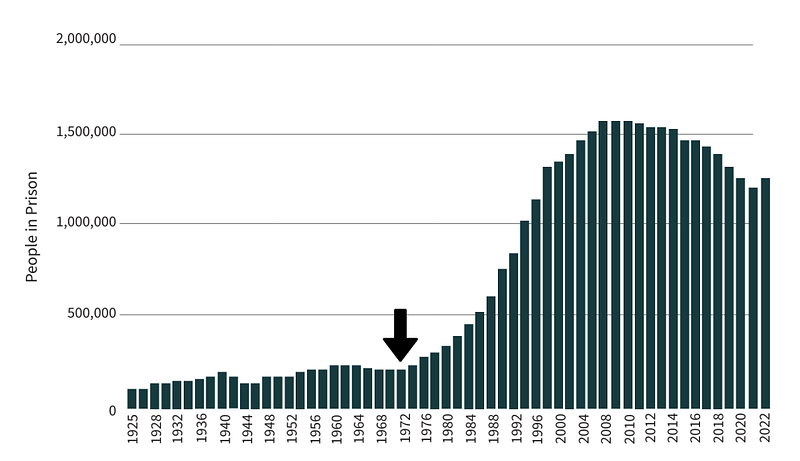

In 1971, the U.S. severed its link to gold (marked by black arrow) in an executive order signed by President Nixon, allowing for unrestricted money supply expansion. Since then, the U.S. national debt and debt-to-GDP ratio have soared. What has also soared during this same period is wealth inequality:

Do you see the correlation?

Again, it’s really quite simple: As the money supply expands (represented by any of the blue bubbles expanding), those who already own scarce assets—whether real estate or a diverse portfolio of stocks—see their wealth appreciate. This, in turn, allows them to leverage their growing assets as collateral to secure new loans, which they use to acquire even more assets. The cycle perpetuates itself, as the very act of borrowing fuels further compounding wealth.

Meanwhile, the average worker’s salary can’t keep pace because wages cannot sustainably rise faster than productivity growth, which will always lag behind money supply expansion.

Here is a graph below that illustrates the increasing polarisation over the same period – an unsurprising consequence of widening class divides:

Interestingly, incarceration rates also show a strong correlation with the abandonment of the gold standard. What’s that all about?

Could it be that declining upward mobility has made profit-driven prisons the default solution for maintaining social stability?

Just as smaller cycles inevitably reach their breaking points within shorter timeframes, so too must a larger cycle eventually come to an end. The difference is that while short-term crises can be temporarily postponed through artificially lowering interest rates or Quantitative Easing (aka bailouts)—expanding “actual money” to mask true systemic fragility— this doesn’t work when the distortions accumulate beyond control.

The collapse of a larger cycle unleashes widespread domestic and international turmoil. These moments are not mere financial resets, but existential ruptures, where populism surges to its peak and the darkest facets of human nature come to the forefront – fueling conflict, war, and social upheaval. It is in the aftermath of these confrontations—after immense and unnecessary suffering—that new treaties are drafted and constitutions rewritten, marking the birth of a new world order.

What I’ve laid out so far has been the cyclical nature of humanity for thousands of years. The looming question is whether we are destined to repeat the same mistakes indefinitely or if we are capable of breaking the cycle once and for all. I, for one, truly believe so – but in order to understand how we need to turn to game theory.

Game Theory

Now that we understand that any bank operating on an interest-based business model must continuously expand credit lending, and that this inevitably leads to solvency issues (and major crises down the road) – let’s examine the forces (aka the incentive structures) that drive real-world banking behavior.

Naturally, anyone looking to deposit money in a bank seeks the highest possible interest rate. While banks can compete by being selective about who they lend to, ensuring low default rates and higher margins, a far easier way to offer higher interest rates than competitors is to simply lower their reserves – in other words, by being less restrictive in issuing more mouse-click credit out of thin air than their competitors.

From a game theory perspective, this creates a race to the bottom: whoever can offer the highest interest rate by lowering their reserves the most wins.

Here’s the anatomy of how it unfolds:

- Starting Point: Full reserve banking – banks act as mere intermediaries, extending credit in a 1:1 ratio with actual reserves.

- Bank 1 lowers its reserves to 75%, figuring that the risk of too many withdrawals at once is low. This lets them offer higher interest rates, attracting more customers.

- Bank 2 lowers its reserves to 50% to stay competitive.

- Bank 3 drops reserves to 30%, further increasing lending and offering even higher interest rates.

- Bank 4 cuts reserves to 20%, and so on.

It’s worth noting that when we talk about reserves in this context, we’re not just referring to the straightforward reserve ratio that regulators track depositor funds and credit extended. We’re also including the more sophisticated strategies banks use to lower their actual reserves. Through derivative products (complex financial instruments) and financial engineering, banks can create the illusion that reserves (their assets) remain intact, while in reality, they are heavily eroded.

This was precisely what happened in the 2008 financial crash, when banks invented the now infamous mortgage-backed securities (MBS) to repackage risky housing loans, masking their true exposure. At peak crisis, sources inside Lehman Brothers say they were leveraged over 40:1*** – which is the equivalent of reserves of only 2.5%. In such a fragile position, even a small drop in asset values of the same size is enough to wipe them out – which is what happened. When Lehman’s CEO Richard Fuld testified before Congress, he stated: “I wake up every single night, thinking: what could I have done differently?” The answer wasn’t exactly a mystery.

As reserves shrink, the system becomes exponentially more fragile. When a bust inevitably occurs, governments step in to bail out the banks under the guise of restoring confidence. Profits remain privatised, losses are socialised. The bankers never truly pay the price, and the cycle repeats – only with a new generation of victims.

Why this model “works”

To understand why this model persists, despite its obvious flaws, we need to look at it from the depositor’s perspective.

Since the structural reality of this system is that governments bail out banks when they fail, the risk profile for depositors is effectively capped – with both a fixed upside and a fixed downside.

- The fixed upside is the interest rate the bank offers in exchange for holding their money.

- The fixed downside is practical reality, since the government will always step in and backstop the system by creating new actual money when banks fail.

In practical terms, this means depositors have nothing to lose (in the short term) by keeping their money in a bank. If things go well, they earn interest. If things go wrong, the government steps in, and the system resets.

But if depositors aren’t losing their deposits in nominal terms, and banks—who always get bailed out—aren’t footing the bill either, then who really pays?

The answer is that everyone without assets ultimately does.

The cost of these bailouts doesn’t just “magically” disappear – it gets shifted onto the broader public, including depositors themselves, through inflation and currency devaluation. When governments create new money to rescue banks, they dilute the purchasing power of all existing money, effectively transferring wealth away from savers, wage earners, and those without access to cheap credit.

But because this process happens gradually, it often goes unnoticed. The loss doesn’t appear as a deduction from a bank account, but rather as a slow, steady decline in purchasing power. Prices rise, wages lag behind, and real savings shrink – all while the system quietly resets, ready to repeat the cycle.

A new model that breaks the cycle

Now, imagine an economy built on a type of money that governments couldn’t create out of thin air to bail out banks.

What would that mean?

In such a reality, banks would almost certainly continue engaging in fractional reserve lending, just as they always have. However, once they inevitably failed (for the structural reasons I’ve laid out), no one would come to their rescue.

Even if governments wanted to bail them out, they wouldn’t have the ability to do so. As a result, banks would finally be forced to learn their lesson and face the full consequences of their risk-taking.

This shift would fundamentally transform the banking landscape by reshaping the depositor’s risk profile. Whereas depositors previously had both a fixed upside and a fixed downside, they would now retain a fixed upside, but face an unlimited downside.

- The fixed upside is the interest rate the bank offers in exchange for holding their money.

- The unlimited downside would arise from the fact that banks’ losses would no longer be socialised. Instead of being bailed out, banks would go bankrupt, and top management would either lose their jobs and/or go to jail.

It’s impossible to predict exactly how this would reshape banking, but ask yourself this:

Would you risk losing all of your savings just to earn a single-digit annual interest rate?

The likely outcome is that fractional reserve banking would transition from a model with a positive expectancy for depositors to one with a negative expectancy – making it mathematically unsustainable in the long run.

The landscape would likely evolve in two key ways:

- Full reserve banking (or something close to it) would become the standard, as depositors would demand proof of full reserves. This shift would likely be enforced through strict government transparency regulations, driven by pressure from the electorate demanding greater accountability in the banking system.

- A shift from interest-based lending (the model outlined) to an equity-based model would gradually take place, pushing fixed-rate interest lending to the periphery.

What does equity-based mean?

Equity-based model

There is no doubt that banks play a crucial role in an economy by connecting those with money, but no ideas with those who have ideas, but no money. This function is absolutely essential – without a mechanism to efficiently allocate resources, the economy would stagnate, and innovation would be severely hampered.

In the interest-based model, this mechanism—despite its fundamental flaws—functions by allowing money (in the form of credit) to be borrowed at a fee (the interest rate) by those with great ideas. In this model, the depositor, whose savings form part of the bank’s reserves (no matter how small), receives a return regardless of whether the borrower succeeds or fails in generating value from the loan.

An equity-based system shifts this dynamic. Instead of depositors acting as passive lenders, they would take on a share of the bank’s investment risk. This means that both profit and risk would be shared between depositors and borrowers – just like how the stock market functions today. If the bank overextended itself and went bankrupt, depositors would bear the losses, potentially losing all their funds.

This shift would leave those with money, but no ideas with two alternatives:

- Hold their money without earning interest. However, in a full reserve banking system, where credit expansion no longer exists, the purchasing power of money would likely appreciate over time. As productivity gains increase over the long-term, money would capture these gains in the form of increasing purchasing power.

- The second alternative would involve taking on more risk for the potential of a higher upside by investing in the equity market – such as stocks (or in a bank-issued investment fund). In this arrangement, profits and losses are shared fairly between investors and businesses, ensuring that risk is borne by those who choose to participate rather than being offloaded onto the public.

Gone would be the days when the rich and powerful—those with collateral—could perpetuate a cycle of extracting wealth from society without contributing anything of real value.

On the horizon, a new kind of liberation would emerge – one where the very mechanisms that once trapped people in wage slavery—forcing them to work more for less—where the gap between reality and dreams only continued to widen, and where the environment and future generations remained the ultimate casualty would finally be dismantled.

In their place, a true meritocracy would begin to take shape – gradually freeing everyone from the shackles of a past system designed, from the very start, on unethical grounds. Something new would emerge – rooted in sustainability, with the potential to break free from the destructive boom-and-bust cycles of the past, steering humanity toward ever higher ground.

Epilogue: Satoshi’s Gift to the World

The year was 2008, and the world was in the throes of The Great Financial Crisis. The housing bubble had burst, leading to the collapse of major financial institutions, widespread foreclosures, and a crippling recession. Governments and central banks responded with unprecedented bailouts and monetary interventions, propping up failing banks at the expense of the public and the savers. Trust in the traditional financial system was eroding rapidly as people witnessed the fragility and corruption embedded within it.

It was against this backdrop of turmoil that, on January 3rd, 2009, a new beginning was quietly forged in the digital realm. An enigmatic figure, known by the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto, mined the first block—aka the “genesis block”—of a new form of money, created for the people, by the people, and beyond the control of those who had betrayed their trust.

But Satoshi did more than just plant a seed for a radically different financial system with this effort; he embedded a message within this block: “The Times 03/Jan/2009: Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks.”

This was not merely a timestamp; it was a quiet act of defiance against the crumbling legacy of the financial system and governments that were once again bailing out banks – institutions that, instead of serving the people, had engaged in reckless and exploitative practices, but were, yet again, not going to pay the price themselves.

Shortly after its birth, the mysterious creator vanished—having concluded that their creation was now in good hands—never to be seen or heard from again.

The gift they left behind was Bitcoin – which is actual money (without the quotes).

Written by independent contributor Petter Englund.

Find more of his writing on Medium.

Follow him on Twitter.

References: *U.S. Federal Reserve, **Bankrate.com, ***”A Colossal Failure of Common Sense” by Lawrence G. McDonald, p. 278.

Stockholm-based screenwriter and sound money advocate. Author of “Made in Cyberspace”, due 2025. Join my quest for worldly clarity!